Meet Solomon, My Dad

by ahjotnaija

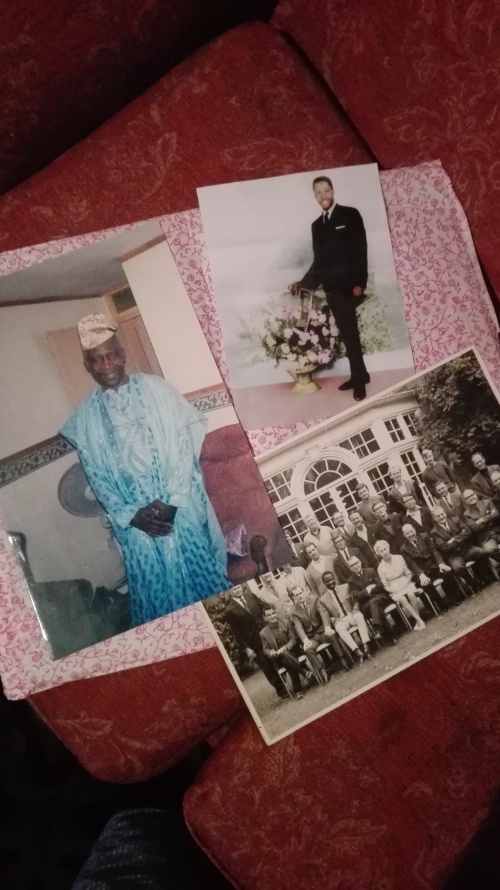

Old and young Solomon

Meet Solomon. Solomon is my father. He was in Dortmund weeks back. With my mother. To welcome the birth of their latest grandchild. My sister had put to bed barely a week prior to the visit. And here they were to see the baby, the mother, and of course to see all of us. This is what they have always done each time a grandchild is born. Solomon was born on 30th July 1942.

After the grandchild-visit came the confirmation of the Job-message via telephone. He was diagnosed with cancer, cancer of the kidney. The stage had not been clearly explained on phone. Really, there are some things that can never be explained good enough for anyone to understand. Cancer is one of them. How do you explain to me that my father might die anytime soon because he is sick? Well, I never will understand. In that state of denial, we started discussing treatment options available to us. The top on the list is chemotherapy. “This terrible word”, I said to myself.

So far, we had only talked on phone, the conversations had always been among me, my brother, my sister and my mother. My mother informed me later she had also informed her sister-inlaw at the time, to which she responded with the highest form of sadness imaginable. It was via the telephone, and yet the sadness couldn’t have been better packaged and shipped on to London.

Back to our telephone conversations. “Did you see my Whatsapp message?” That was my mother to me on a Whatsapp call. “Yes. I saw it. What is that?” “Well. You saw what is inside. Abi o ri ni?” “I did. I will call you back.” I rang up Tunde, who confirmed he received same message. And my sister too. Apparently, they had been discussing the sickness. “Well. Chemotherapy ni won ma se.” “No way. They want to kill him. He is too old. For his age. No. What did he say? Has he agreed to undergo the treatment?” “That is still being discussed. If that is the only option he will have to, at least a chance of survival is still there if he went for it. If not, he is good as dead.” “So. What do you suggest? You sha cannot be against one without bringing an option to the table.” “I don’t know. Has he agreed to it? It’s his life on the line here. What are we saying here? Is she that excited to become a widow!? Listen, if he doesn’t want it, then let him be!”

The conversations went on for days unend. I read up on chemotherapy. I read up on kidney cancer. It all sounded so terrible a sickness as I had imagined. Chemotherapy is not great either. The side effects almost made me throw up. Abi iru ki re!?

I returned from work one evening like that, I met Mrs Brinkmann, my good old neighbour. We greeted. She opened the housedoor. Sisi, her old dog entered, she struggled with the dog-rope and getting her key out of the doorhole. I helped, as much as I could. She valued her independence. We were in the staircase.

“So, Ibu, how are you?” “I am not fine, Mrs Brinkmann. My father has got cancer. Kidney cancer.” Her countenance became sadness. “I am so sorry, Ibu. He is such a fine man. See how he hugged me when last he visited you. Telling me everything will be fine, as if he knew I had problems. He is such a kind man. So sad he has been caught by this terrible thing. Ibu, I am so sorry.” She continued, “Ibu, did I tell you our neighbour has got brain tumour?” “Yes, you did, Mrs Brinkmann. I was about asking you if she was getting any better. How is she responding to treatment?” “Ibu, forget it. She’s 87. Age is not on her side. Plus, that’s brain tumour we talking about. She’s got brain cancer, Ibu! Right in her head! Poor woman.” “No wonder she had such terrible headaches almost everyday. She used to tell me each time we meet on her dogwalks.

By the way, what will happen to her dog? Will he be taken to a home? I hope he is not killed for lack of anyone to care for him”. “No. No. No. Ibu, that will not happen. The last time I spoke with Heidi, she told me the children had come for the dog. They did not bring him to the hospital because they feared he might be traumatised. He is too young to see his owner in such a sickly condition.” “Oh. So sad. Did you not say it was Heidi who called the emergency when she discovered her condition needed immediate attention?” “Yes, Ibu. She informed the children too.”

She continued. “Thank Goodness for Heidi. What would have happened if not for Heidi! Even me, she helps out alot. Oh, by the way, Ibu, thank you for spreading my clothes on the line. You needed not do that. I thought I told you so.” “Yeah. I know, but I felt I could do that for you too. I brought it up from the washroom, I checked my time, it was not too late yet. I quickly spread and pegged them before I went in. I jumped into my bed almost immediately to catch some sleep.” “Oh. Thank you, Ibu. You are such a darling.

I returned to the dog. “So, the dog was not taken to the hospital?” Mrs Brinkmann spoke about the woman. “I heard she refused to be touched or given any drug or treatment whatsoever. I guess she is bent on leaving us. So sad, Ibu. I pity her.” “Yeah, so sad. She’s been through alot.” “She might be brought to the hospice anytime from now. I am not sure she wanted the hospice in Mengede. I was told it is such a terrible hospice. But what can she do now? In her condition, she will definitely be brought to the nearest hospice. She couldn’t be part of the decision where to spend her last days. She was unconscious, you know, when the emergency arrived. I am not sure she’s coming out alive.” “She lived a good life.” “Yeah, that’s true. Ibu, I am so sorry about your father. Chemotherapy is the only option, even if terribly feared, you might have no choice than to let him do it. It’s his chance. He should take it.” “I don’t know, really. I don’t know. Good night Mrs Brinkmann. Thank you for your time.” “Good night Ibu.”

We will have to visit in London. To show moral support. He’s been such a good father. He needs us in this difficult time. I was as busy as hell. My brother too. My sister had just put to bed. How shall we get to visit him? I was decided in my mind to pull off a visit, no matter what. Few days before my leave, I submitted my application for a UK visa. It was granted. One thing led to the other, and the next day I was standing at Shifford Path where my parents live. I knocked on the wrong door for a while. When nobody opened, I called my mother’s mobile.

“What are you saying?… Open the door biti bawo!? The door is open. Come in… Did you say you are at our door? This is London number you are calling with… Ah. I thought Jumoke was joking when she said you were on your way. Olorun a gba e. What kind of child are you… Number 21. Where are you knocking… The neighbour. Ah. He has a giant dog… Come over to Number 21. The door is open…” I dropped the call, walked over to Number 21, and there she was standing at the door to welcome me home. I greeted. My brother-inlaw greeted. My nephew was fast asleep. “Where is daddy?” “Upstairs. In the bed. Not sleeping though.”

I went upstairs to tell him I have arrived to spend Christmas with him and his wife. He jumped out of the bed to welcome me. He was full of smile. I saw happiness. More than that, I have come to meet him. I want him to tell me everything he knows about his family. The next day we started with his mother.

She was a gentle woman, loving mother and the epitome of beauty. She was the best mother anyone could wish for. She must have been born between 1918 and 1920. An exact year of birth was not easy to arrive at. In the course of our discussion, I decided to place the birth of my paternal grandmother around the started years. The reason being this: When she got my father, her first child, she probably was 21 years old. According to Solomon, my father, it was usual for women of that time to be married off early, around 21 years or younger. Allowing that she was married at 19/20 years, depending on how soon she became pregnant with my father, then she must have been 21 years old when she gave birth to Solomon in 1942. Of course, she could be older if we allowed in our calculation that she suffered delays in becoming pregnant. So, if we insist that she was 21 when she got her first child, then add the possibility of delayed pregnancy, it will be that she was married much younger than 21. If our calculation was right, minus delayed pregnancy, then it must be that she was married around 20/21 years of age. In any case, according to Solomon, his mother could not have been 100 years old if she was alive today.

She gave birth to other children. She had four children in all. In this order: Solomon(born 1942), Dada aka Jonwo (1945), Iyabo aka Iya Mushin(1947), Modupe aka Iya Ketu(1949). She died of cancer of the uterus. According to Solomon, if only he knew earlier he could have arranged for the uterus to be removed. He explained further. It was not as if she could still give birth. She was done with child bearing, so the reasonable thing to do was to remove the uterus, at least if that would have saved her life. The cancer was found out too late though. So, my paternal grandmother had little or no chance of survival. She died in shortly after Solomon’s return from the UK. It was in part due to the sickness of his mother he decided to come home in that year. He had left for the UK in 1964 with a work/study voucher after he finished from Yaba College in 1963.

He must have loved his mother so well. I could hear it as he talked about her. He said these things about her:

“Mama used to be my bank. I was the treasurer of our football club back then at Arokolaran. I was chosen to keep the moneybag because my integrity was proven. I am a disciplined person, not given to nonsense of that time. So when money was given to me, I took it to Mama. (Solomon referred to his mother as Mama during the whole talk between us both. I could practically touch the love in his voice for the woman as he spoke about her). And when we needed the money, Mama brought it out and gave it to me. I then took the money to my club. There were banks back then, of course. Standard Bank, Barclays Bank, now First Bank and Union Bank respectively, but we did not own a bank account with any of these banks. Mama kept the money for us.”

When he talked about his younger stepbrother, he came back to talking about his mother, to underline the kind of pure love this woman embodied. This is what he said:

“You won’t believe it but it’s true. Do you know when I told Mama that I will not be responsible for Tunde’s education anylonger, she broke down crying. She was crying and begging me not to withdraw my financial support for her stepson. This is a child, who apparently was unwilling to enjoy education, his mother said nothing, although she heard Mama crying and begging me, when I brought Tunde’s report card which a family member had fished out from the dustbin. He had thrown it into the dustbin because he did poorly in school. Mama was such a simple personality, full of love for all. Such a pity you did not get to know her.”

We went on to talk about his father. Solomon’s father worked with PWD, the Public Works Department in Lagos. My grandfather had moved with his parents, my great grandparents, to Ijoko-Ota in present day Ogun State from Igasi-Akoko in search of greener pasture. Solomon said it was for the same reasons people moved from Nigeria to London these days that informed the decision of my great grandparents moving to Lagos. Lagos was London back in those days. At first, they settled in Ijoko-Ota. A farm settlement was founded, from where they later moved to Arokolaran and Mushin Akala Area in Lagos. Both Solomon’s maternal and paternal grandparents had strong roots in these places. They settled there. It was there in Lagos he was born.

His relationship with his father was cordial. Just like that of any father of that period in time. Solomon talked of fathers of this period as being ‘terrible’. They were like Gods. He narrated of a father who cursed his own son, and the son ran mad. The said father was angered that his son, who had forgotten him when things were rosy, dared come to him to tell him that fate issued him a bad card at that point in time. The father placed a curse on the ungrateful son.

What prompted this narration? I asked him why he did not prevail upon his father to not marry a second wife. Solomon’s response was great shock. I could see it on his face and hear in his voice the abomination I wanted him to commit. He said: “That would be pushing too much insult way too too far!” He then narrated of the father who cursed his own son.

Solomon loved and took care of his father. He ensured he was operated when he had health issues that necessitated surgery. He pleaded with him to give up drinking, which his father did not do. His father died not long after. According to Solomon, he was a good father. He probably would be around 110 years old or older if he was alive today, but certainly younger than 120 years. I placed his birthday around 1905.

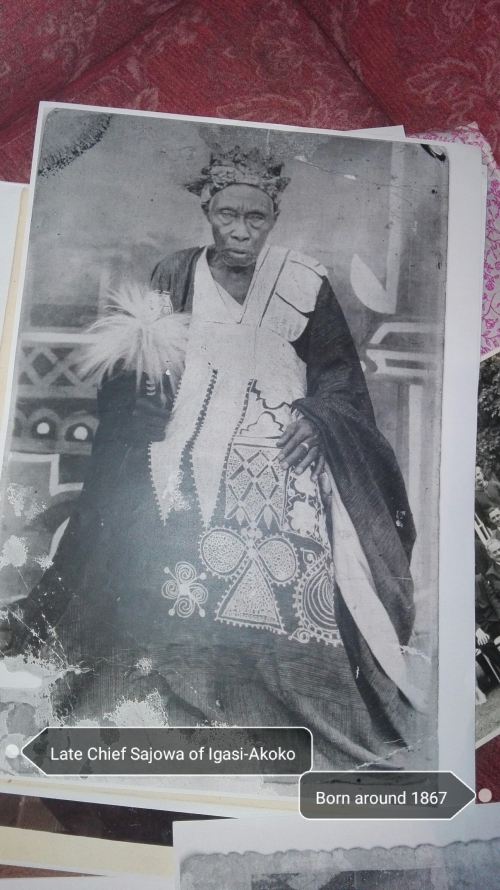

There were many pictures. Solomon stood up from the couch, looked somewhere under the shelf in the living room and brought out pictures, well wrapped away in big papers. He started showing them to me and we kept talking. More sturves to talk about came up. We happened on a picture of his grandfather, my great grandfather. We talked about this man. From my calculation, if Chief Sajowa, my great grandfather gave birth to his first child when he was about 30 years old, he must have been born around 1867. This is what Solomon said about him:

“That is Ajagunna. Ajagunna is the family name. It’s a chieftancy title and the family name. He is Sajowa. Chief Sajowa of Igasi-Akoko. He came from a Muslim background. There was one of his sons named Jacob Aliu. His family moved from Ikare-Akoko to Igasi-Akoko to settle there. He had six children. My father was one of his children. He was buried in Igasi-Akoko when he died.”

Chief Sajowa of Igasi-Akoko, Solomon’s grandfather, born around 1867.

Solomon met his wife, Mercy, when he brought the corpse of his mother to Igasi-Akoko for burial in her ancestral home. He saw the young woman and decided he was going to marry her. She was reluctant at first. Solomon said he wasted no time in moving on to other ladies to try his luck. Then Mercy came back to him and agreed to marry him. We had a good laugh about ‘wasting no time’. Both were married in 1981. The couple had their first child in 1981(my brother Tunde), the second child was born in 1983(my sister Jumoke) and the third and last child was born in 1985. That’s me.

Solomon is grandfather to six grandchildren. He lives in London with his wife.

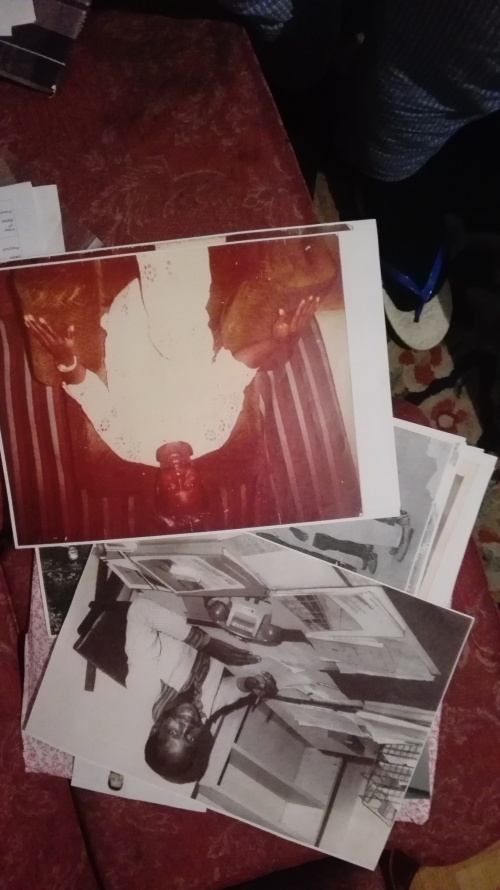

Above: Solomon in his office as Technical Manager, BEWAC Construction Company. Below: Solomon at his engagement/marriage ceremony in Igasi-Akoko.

Hi Ajaguna, nice story about your family history. It’s so sad your dad suffers from that disease. I hope it’s still in its early stages. If yes, he may want to try natural healing. Using food as medicine cures some forms of cancer as we read online. All the best for him. I’m sure his grandchildren and children still need him around.

LikeLike

Thank you ogbonwande for your kind words. We are trying some alternative medicine. We strongly hope it works. Happy New Year.

LikeLike

Captivating story

LikeLike

Nice story Gbemi sorry that at last………

LikeLike

Gbemi sorry for d lost of dad. accept my condolence

LikeLike

Cpntinue to Rest in peace dad. What a great man you were!

LikeLike